[Disclaimer: I have the mathematical ability of a dead trout. Still, I enjoy a layman’s appreciation for the poetry of numbers. When I studied symbolic logic in college, I loved to write vast, swooping proofs, glorious things to contemplate—and awesome in their failure to make any sense whatsoever.

The point is— and I address this to my friends who are mathematicians—if I get carried away, please don’t yell at me. For my part, I’ll try not to break math.]

The Problem

I’ve been feeling down these past few days. Lately it seems like Entropy and Futility have perched themselves squatly on my shoulders for a good, long visit. My weight, my writing, my classroom, even my side of the bed: like the Red Queen in Looking-Glass Land, I have to run as fast as I can just to keep them from falling apart.

The Consolation

At a time like this, I take comfort in a statistical phenomenon called Regression To the Mean. I first learned about it from a podcast by Geoff Engelstein, a game designer and generally really smart guy.

(If you want to hear Engelstein’s original segment [which you should—it’s awesome], it’s here. And here’s the site of Ludology, a board gaming podcast that he co-hosts with other really smart guy Ryan Sturm.)

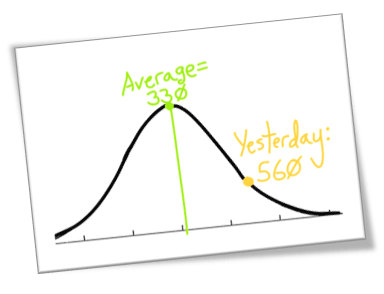

Let’s say you and your old chum Clem play a nightly game of Scrabble, and your average score works out to 330. Yesterday, however, you were an unstoppable monster of Scrabble brilliance, finishing with an impressive 560 points. You believe this represents a Scrabble breakthrough for you, and from here on in, it’s all Mai Tais and lobster on the pro-Scrabble circuit.

Clem is not convinced.

A Short Play About Math

You: 560! What a whopping score! Surely I have made a great leap forward in my Scrabble skills. I can almost taste the Mai Tais and lobster now.

Clem: I am not convinced. Your 560 is impressive but promises little, statistically speaking.

You: It is you who promise little, Clem.

Clem: I think not. Observe this bell curve chart I have prepared; it shows the probable distribution of your Scrabble scores. I have graphed your average score of 330, as well as last nights’ 560.

You: Ok, but-

Clem: Shut your pie-hole, chum, and look at the curve. Please divide it into two unequal halves—the set of scores less than 560 and the set of scores greater.

You: Very well; good thing I always carry a whiteboard marker. There… we… go.

Clem: Which side is larger—the green or the yellow?

You: Do not patronize me, Clem. The green is obviously larger.

Clem: Indeed. If we imagined reshaping it into a kind of target, it might look like the one below. If you threw a dart at it, what section would you probably hit?

You: The green, of course—there’s so much more of it than the yellow.

Clem: Exactly. And I don’t want to belabor the point—

You: …too late, chum…

Clem: But consider this jar of jellybeans; which are you more likely to pull out at random- green or yellow?

You: Green again.

Clem: Exactly. Is there a chance that you’ve had a major Scrabble breakthrough? Yes—and perhaps time will tell. But it’s far more likely that you just had a good game. In the bell curve that your 330 average describes, 560 is a possible, but unlikely, score– and totals higher than that are scarcer still. Fortunately for me, your next score will almost certainly be lower than 560.

You: Ah, well; I’m allergic to lobster anyway.

So why do I find this comforting?

Because it reminds me that one or two or three instance of anything do not necessarily make a pattern. Certainly they do in art, in books and movies, but those things are formed and finite, stand-ins for life, not life itself, which is open-ended and wonderfully formless.

It reminds me, when I’m laid low by a bad day of writing, or an ugly number on the scale, or a lesson that goes wrong, that as bad as it feels, it’s only one instance. A frustrating writing experience doesn’t mean that I’m becoming a worse writer. A day of stupid fights with my son doesn’t mean I’m tanking as a dad. I’m still the same writer, father, teacher that I’ve always been– I just had a bad day.

Change is hard, and blessedly slow. We are who we are and, generally speaking, it takes a lot of sustained effort to make any lasting difference at all.

We’re never as good as our best day– but we’re never as bad as our worst.

And that is what I have learned from Regression to the Mean.

One more thing:

“Regression to the mean” also sounds like what happens shortly after the meek inherit the earth.

I didn’t have anywhere to put that joke, so I’m just sticking it here.

I tried to reply before … let’s see if this actually goes through. A very smart and snappy read … and one I particularly needed to read today…

Thanks, Rob– it’s the kind of thing that never FEELS true– butthe numbers say otherwise. Sorry you’re having that kind of day…